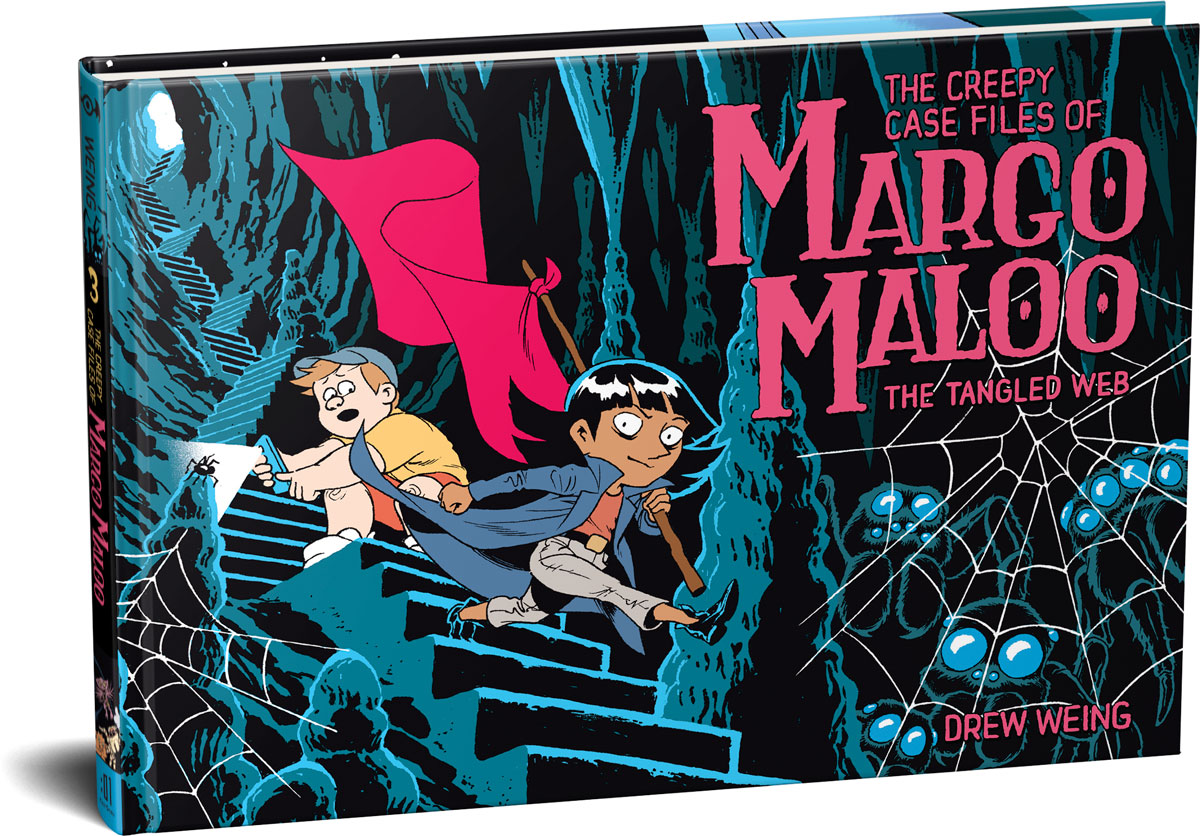

Set to Sea pg. 98

Happy Bloomsday. If you haven’t read Ulysses, you can go read Richard Thompson’s version, you won’t even need the reader’s guide.

More thoughts about teaching art:

One of the kids in our class was an almost disturbingly canny 12 year old. When I sat down with him and looked at his comics, I learned pretty quick that he was onto any hint of false positivity, even though he drew pretty much as well as any of the kids his age. I would say something like, “Hey man, these poses look great! They really capture a lot of energy!” and he would raise his eyebrow and say in a pitying fashion, “You really think these are great? They’re just stick figures.” Most of the other kids – even the older ones – as soon as I sat down next to them, would be thrilled to describe the action happening in their comics blow-by-blow (useful, since it was hard to puzzle out sometimes.) This kid would just sort of embarrassedly mumble that it was only some guys fighting. He had a sketchbook of carefully copied Naruto pictures, but would only draw stick figures of his own creation. He actually drew less and less as the class went on. Eleanor said that in one of her sessions, he said to her, disappointed: “I thought you were going to teach us how to draw cool.”

He might have been one of the smartest and most self-analytical kids I’ve met, and he will never be an artist.

Eleanor and I were talking about what makes some kids into artists and some not, and the concept of early and late bloomers. Almost all kids start out as little sociopaths who live inside their own heads, but at some point most start becoming normal adults with empathic responses and an idea of how they fit into the world. I was definitely a late bloomer, socially – I think I was still running around in the woods shooting lasers at imaginary enemies until early high school. And somehow I kept drawing into adulthood. So I’m speculating, is there some sort of critical hump in late childhood, where most kids would start comparing their drawings to peers (and professionals,) realize they weren’t up to snuff, and drop the whole thing? And late bloomer types, by sort of sailing obliviously over this hump, actually put in the needed hours and hours of drawing time to become good at it?

Hopefully, you do bloom at some point, though. Maybe today, it’s Bloomsday after all.

Much of what will happen in your little friend’s career will be influenced by things outside his own abilities. I think talent can form a great artist, but drive and persistence can overcome the former and create a successful one. To anyone who asks how I can draw “so well” (not, IMO), I tell them practice is the key. I’d pitch your talent and craftsmanship against many wildly successful cartoonists any day. Who knows, that smart kid could be the next Gary Larson or Bill Amend, maybe thanks to your influence.

I agree with Dave that practice is a major, often unforeseen, element to excelling in any craft. There seems to be a point in developing any craft where most people realize they aren’t progressing at the rate they hoped to. At this point they have to face the “make or break” decision of putting the requisite time in and continuing or ceasing pursuit of the craft in question.

Why do some people stick it out and continue and others don’t? I think one major reason people stick with a given craft is that despite adversity their minds find the pursuit and exercise of the craft satisfying in a way that little else is. Anything that’s frustrating, be it drawing, performing music, getting in shape, quitting smoking, beating a video game, or even opening a pickle jar, an individual’s mind either elects that it’s worth coming back and trying to overcome the adversity or it’s not.

Another factor is how much motivation or resistance a person gets from their environment while pursuing their goal. Certainly artists have prospered despite being raised in environments that weren’t encouraging (or in fact downright hindrances), but almost certainly many more come from environments that nurtured their progression.

My take home message is that by teaching a group of kids to draw you are providing a positive environment that for most will be a significant boost to helping them progress their talents. The unfortunate truth of teaching is that you won’t be able to help all your students “over the hump” of adversity the way you would like. This is often a tough pill to swallow, but its important to focus on all the good you are able to accomplish as well.

Eh, that kid was not hearing anything about practice. He knew that his pictures did not look like Naruto right now, and he sure wasn’t going to churn out the – what do they say, you have to get 10,000 bad pictures out before the good ones start coming? – anyway, he was too smart to waste his time. I’m saying, a little obliviousness at the right time might be a good thing.